SI-TM: Reducing Transactional Memory Abort Rates Through Snapshot Isolation

- Hide Paper Summary

Link: https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2541952

Year: 2014

Keyword: SI-TM; Snapshot Isolation; Multiversion CC

Conflict Resolution: Lazy

Version Management: Multiversion

R/W Bookkeeping: Not mentioned; Logging?

This paper proposes a multiversion TM design with weaker snapshot isolation (SI) semantics guarantee. Canonical HTM designs usually provide conflict serializable guarantees. One one hand, several snapshot isolation specific anomalies make programs written on other HTM platforms non-portable. On the othre hand, by omitting read set validation, long reading transactions may suffer from less aborts. In addition, less hardware resources are dedicated to maintaining transaction metadata, as fewer states are needed to validate.

One distinctive feature of SI-TM is the usage of multiversion in HTM. The second feature is timestamp ordering (T/O) based backward OCC validation (validate with committed transactions). Although these two approaches to concurrency control are not uncommon in software, in hardware they are relatively rare.

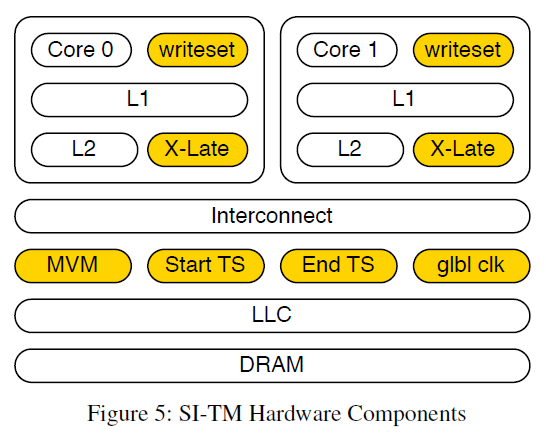

SI-TM relies on a multiversion device called MVM (Multiversioned Memory) to provide virtualization of physical addresses. On a CMP with private L1 and shared LLC, the MVM is placed in the uncore part of the system, right before the LLC as an extra address virtualization layer. MVM translates physical cache line address and version pair (addr., ver.) into a pointer to the versioned storage. The pointer can then be used to probe the shared LLC, or, if LLC misses, to the main memory. L1 and L2 use the physical address from TLB as the tag, while LLC uses the true physical address.

When a cache line is evicted or when a request is sent, the message must go through MVM using the physical address and the version in the context register to obtain the physical address for probing LLC and DRAM. This is somehow awkward, because when invalidation message is received, there is no backward translation mechanism to invalidate the corresponding cache line in private L1/L2. In addition, the transaction is not fully virtualized, because now the physically tagged L1/L2 is actually virtually tagged. When a context switch happens, the speculative cache lines must be flushed or written back.

What I did not understand in the above figure is the placement of begin and commit timestamp. Conceptually they belong to the executing transaction, which should be part of the processor’s private context. In the figure it is drawn in the uncore part of the procssor, implying the begin and end timestamp are shared across processors. Update: It is a vector of timestamps. So the timestamp is in the uncore part of the CMP. Can we access these timestamps efficiently?

As virtual memory uses TLB to accelerate translation, there can optionally be a corresponding lookaside buffer that’s checked with L2 search in parallel. Recently accessed (addr., ver.) pairs are stored, and the physical address of the version’s storage is returned.

On transaction start, the processor obtains a begin timestamp (bt) from the hardware global counter by atomic fetch-and-increment. Commit timestamps (ct) are not determined yet. All cache lines involving the commit timestamp before transaction commit use a transient ct, which is preserved by MVM, and marked as invisible.

On transaction load, the processor first probes L1/L2 using the physical address. If L1/L2 miss, then the request is sent to the MVM. MVM searches its version list using the (addr., ver.) pair (versions are kept as an array in the uncore part), and returns the physical address of the oldest version that is below the bt of the requesting transaction. Keeping the timestamp of the returned transaction below ct avoids a later transaction’s commit into the same address being observed, even if the latter was flushed to the MVM, as MVM renames the cache line to a larger version. No read set is maintained.

On transaction store, the processor first loads the cache line as a normal load, and apply the store in L1 cache. The store address is also inserted into the write set. No cache coherence message is sent.

On cache line eviction (note that there is no invalidation on uncommitted dirty line as MVM does not perform reverse translation; invalidation on read-only line is propagated from LLC without any problem), if the evicted line has transactional bit set, and is dirty, the MVM allocates a new version using the transaction’s transient version number. The uncommitted line is written into the physical address returned by MVM.

On transaction commit, the write set is tested. If the write set is empty, the transaction commits immediately with zero overhead, and the commit always succeeds. Otherwise, the ct is obtained from the global counter. Note that the paper does not mention whether the counter should be incremented after obtaining ct, because there is a race condition here that needs special care. See below for a detailed example. Then, for each dirty line in the write set, either the line is already in MVM, or the processor evicts it to MVM. In both cases, the dirty cache line is assigned ct as its version number. In the meanwhile, validation is performed as cache lines are written back. Write-write conflicts are detected, if the most up-to-date version on the address is greater than the bt, as the snapshot no longer holds as a consistent image. The transaction aborts in software by rolling back all written lines from MVM, and clearing all hardware structures.

The above commit protocol has an undesired race condition that may incur inconsistent reads. Assume that data items A, B were at timestamp 99. The global timestamp counter was 100.

Inconsistent Read Example:

Txn 1 Txn 2

Commit @ 100

Begin @ 101

Store A

@ 100

Load B

@ 99

Load A

@ 100

Store B

@ 100

Finish

FinishTransaction 2 starts during the commit stage of transaction 1. The begin timestamp prevents transaction 2 reading from commits that start after its transaction begin. Reading transaction 1’s half committed data, however, is incorrect.

Not allowing new transaction to begin during any commit solves the problem. This, however, limits parallelism as transaction commit blocks the creation of new transactions globally. A better solution is to increment the global counter by some Δ on commit, and the committing transaction uses the timestamp after increment to write back. In the meantime, newly started transactions could only use timestamps within the Δ range. Since the Δ range is below the committing transaction’s write timestamp, transactions starting after the commit point can always observe a consistent snapshot. New transactions still needs to be blocked if more than Δ new transactions begin. This, however, is relativelu rare, as validation and commit are considered as fast in most cases.

Races between validation phase and commit phase may also arise, if validation and commit is not serialized as a single critical section.

Racing Validation and Commit Example:

Txn 1 Txn 2

Begin @ 98

Begin @ 99

Commit @ 100

Commit @ 101

Check A

@ 99

Check A

@ 99

Store A

@ 101

Store A

@ 100

Check B

@ 99

Check B

@ 99

Store B

@ 100

Store B

@ 101

Finish

FinishAfter execution, A, B is of version (100, 101), which is not reachable by any serial execution. Making check and store operations as a single atomic unit could solve the problem.

Garbage collection is conducted lazily as new versions are created on a cache line. To infer the oldest active version that MVM must maintain, a priority queue of action transaction begin timestamps is maintained. Every time a transaction commits and creates a new version, it reads the current oldest begin timestamp (obt), and removes all versions that has a timestamp smaller than the reachable version using obt.

To reduce storage/lookup overhead of infinitely many versions, MVM supports up to four versions on each cache line address. If a transaction creates the fifth version on commit, the oldest version is discarded. If a transaction reads a non-existing version, the transaction is aborted and restarted using the most up-to-date begin timestamp.