Improving the Performance of an Optimistic Concurrency Control Algorithm Through Timestamps and Versions

- Hide Paper Summary

Link: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/1702279/

Year: 1985

Keyword: BOCC; Version validation

Conflict Resolution: N/A

Version Management: N/A

R/W Bookkeeping: N/A

Classical BOCC validates read sets serially by intersecting the read set with write sets of earlier transactions (i.e. those who entered validatin & write phase earlier than the validating transaction). To reduce the number of write sets to test, a global timestamp counter is used to order transaction write phase and begin. The value of the counter indicates the most recent transaction that finished the write phase. In this scheme, since validation phase and write phase are in the same critical section, the order that transaction finishes write phase is also the order they enter validation. Every time a new transaction begins, it takes a snapshot of the counter, ct1. All write phases that finish after ct1 (and hence have a finish timestamp no less than ct1) can potentially interfere with the new transaction’s read phase. On transaction commit, it first waits for the previous write phase currently in the critical secton to finish, then enters the critical section, and take a second snapshot of the timestamp counter, ct2. All write phases that start before ct2 (and hence have a finish timestamp less than ct2) can potentilaly interfere with the new transaction’s read phase. The new transacton, therefore, validates all write sets that have a finish timestamp between ct1 and ct2.

This paper seeks to improve existing BOCC algorithms from two aspects: using version based validation, and using multiversion. We explore these two directions below.

Version-Based Validation

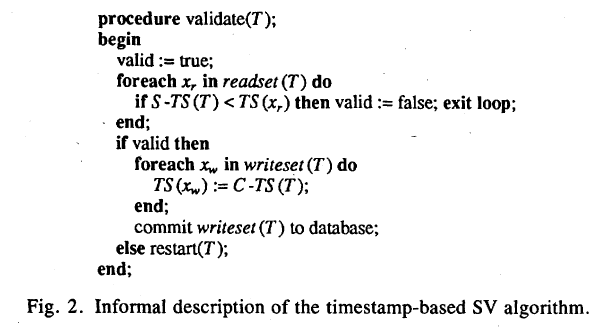

Instead of performing set intersections, which requires (# of write sets * # size read set) hash table probing (we assume write sets are implemented as O(1) probe time hash table), timestamps are assigned to each data item in the system. During the serial validation phase, transaction obtain commit timestamps (ct) from the global timestamp counter. Then, in the write phase, they update timestamps of items in write sets to ct. Furthermore, when transactions begin their first read operation, they obtain a begin timestamp (bt). Validation is performed by comparing the timestamp of data items in the read set with bt. If the timestamp is greather than bt, then obviously some transaction’s write phase has written into it after the validating transaction started.

Figure 1: The Version-Based Validation and Write Back

The original version-based vaidation in the paper, however, is incorrect. As shown in Figure 1, the write phase first

obtains ct (C-TS(T) in the code snippet), then updates timestamps of data items, and eventually writes back

dirty values. A new transaction that begins after the committing transaction obtained ct but before it finishes write back

can make the schedule non-serializable. An example is presented below:

Non-serializable Schedule Example:

Txn 1 Txn 2

Commit @ 100

TS(A) = 100

TS(B) = 100

Begin @ 101

Store A

Load A

Load B

Store B

Finish

Commit @ 101

Validate A

TS(A) < 101

Validate B

TS(B) < 101

FinishIn the above example, both transaction 1 and 2 commit successfully. A cycle consisting of two dependencies, however, can be identified. One is 1->2 RAW on data item A, another is 2->1 WAR on data item B. The crux of the undetected conflict is that, if ct is obtained “too early”, i.e. before updated values of data items are written back, then risks are that new transactions may begin without being aware of the ongoing write phase. The atomic fetch-and-increment to obtain ct can be thought of as a contract which guarantees that after this point, read operations to any data item in the write set must return the updated value (till the next overwrite). Failing to observe this contract will result in new transactions not being able to read the most up-to-date value although they have been logically committed.

To fix this problem, the acquisition of ct must be postponed, till the point that all write back completes. To see why

this works, consider concurrently spawning transactions. They either obtain bt before the committing transaction

obtains ct, or after it (since it is an atomic operation). In the former case, there is the risk that the read phase

of the newly spawned transaction overlaps with the write back of the committing transaction, resulting in RAW and WAR

dependency cycles. Such violations, however, are guaranteed to be caught by validation, based on two observations:

(1) The new transaction will only start validation phase after the committing transaction finishes updating

timestamps of data items, because the validation and write phase is inside a critical section. This observation

suggests that the new transaction must be able to see updated data item timestamps. (2) The new transaction’s bt

is smaller than the committing transaction’s ct, and hence smaller than data item’s ct if conflicts exist. This can

be detected by validation. Note that false conflicts are possible as in the example below, but no conflict can be missed.

In the latter case, the reasoning is more straightforward. In the committing transaction’s program order, we have

write back -> obtain ct; In the new transaction’s program order, we have obtain bt -> read phase. In addition,

we assume obtain ct -> obtain bt. The overall ordering of events is therefore

write back -> obtain ct -> obtain bt -> read phase. No dependency cycle can possible happen, as the new transaction

is guaranteed to read updated value.

False Conflict Example:

/*

In this example, transaction 2 only reads updated values of transaction 1.

Transaction 2 fails validation, nevertheless, because its bt is smaller than

transaction 1's ct.

*/

Txn 1 Txn 2

Store A

Store B

Begin @ 100

Load A

Commit @ 101

Load B

TS(A) = 101

TS(B) = 101

Finish

Commit @ 102

Validate A, B

TS(A), TS(B) > 100

ABORTBy using version validation, the number of operations is reduced. Assuming that version storage is implemented as an hash table with O(1) probe and insert time complexity, the number of probe operations for validation is merely the size of the read set. In addition, version update during the write phase requires (write set size) insert operations. Overall, the cost is (read set size + write set size). If we disallow blind writes, then the write set is a subset of the read set. We can therefore rewrite the overhead as at most (2 * read set size). Compared with the classical BOCC implementation, the reduction of overhead is quite significant.

Multiversion OCC

Another direction for optimizing OCC validation is to use multiversion. This paper bases its discussion on a multiversion 2PL called the CCA (Computer Corporation of America) Version Pool algorithm. Transactions are classified into update transactions and read-only transactions. Update transactions use 2PL for serializable synchronization, and they always access the most recent version. At commit time, update transactions obtain ct, and then create new versions as they write back. The timestamp of the new version is the ct of the committing transaction. No validation is required, as update transactions acquire read locks during the read phase and write locks during the write phase. Read-only transactions, on the other hand, do not acquire locks. Instead, they obtain bt from the same source as update transaction’s ct. Read operations are performed on the most recent version less than bt. No validation is required for read-only transactions, as they always see a consistent snapshot. Note that the same race condition between a comitting transaction and newly spawned transaction can happen as we discussed in prior sections. No solution is provided.

Multiversion can also be leveraged by OCC to improve read throughput, as read-only transactions are guaranteed to succeed. In the MV-OCC scheme, instead of acquiring read/write locks, transactions read optimistically and buffer writes as they are in a version-based OCC. During the serial validation and write phase, version validation is performed as usual. New versions are created with timestamps being ct as update transactions write back dirty values. Read-only transactions obtain bt only, and read the most recent version less than bt. Care must be taken that the race condition between committing transactions and newly spawned transactions can still be resolved by postponing the increment of the global timestamp counter. Before write back starts, the committing transaction reads the current global timestamp as ct’ without incrementing it. The timestamp of versions it creates is ct’ + 1. At this stage, all newly spawned read-only transactions cannot read half-committed values. On the contraty, update transactions may obtain a bt which is identical ct’, and fail validation, because the data item they access has at least a timestamp of (bt + 1). After the write back, the global timestamp is atomically incremented. Consistency is preserved because transactions spawned after this point will see fully committed write sets.

Note that the above technique only applies to serial validation and write phase. If multiple instances of write backs are present, they may obtain the same ct’ and hence use the same commit timestamp (ct’ + 1). The completion of any write back will increment the global timestamp counter, publicizing all concurrently committing write sets even if they may have not been fully committed.