A Lazy Snapshot Algorithm with Eager Validation

- Hide Paper Summary

Link: https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2136071

Year: 2006

Keyword: LSA-STM;

Conflict Resolution: Eager

Version Management: Lazy

R/W Bookkeeping: Set

This paper provides another view to the Backward OCC algorithm. The classical way models BOCC problems as preventing overlapping read and write phases via either timestamps or set intersections. This paper proposes an interval-based approach. Each transaction, at the transaction beginning, is assigned a valid interval of [CT, +∞). Each instance of the data item also has a valid range. The lower bound of the valid range is defined by the commit timestamp (ct) that creates the particular version of the data item. The upper bound of the valid range is defined as the ct of a later transaction that overwrites the item. The overwrite of a data item by a committing transactions updates the upper bound of the previous version and the lower bound of the new version atomically.

Transaction commits are serialized by a global timestamp counter as in other BOCC algorithms that use the counter. As transactions access data items, they intersect their intervals with the valid ranges of data items that they access. If the resulting interval is non-empty, then the access is guaranteed to be valid, and requires no extra validation. The intersection, however, can become empty because the data item’s lower bound is larger than the transaction’s upper bound (the reverse will not happen, because if the transaction could not read an item which has been overwritten before it starts). In this case, the transaction validates the current read set, and “extends” the upper bound of its interval to the current global time.

A transaction extends its upper bound by performing an incremental validation. For all versions in its read set, it tests whether the version’s most up-to-date upper bound is smaller than the current global time (the most up-to-date version has an upper bound of +\∞). Note that an overwrite on data items will update both the previous version’s upper bound and the new version’s lower bound atomically. If the upper bound of all data items is still no smaller than the current global time, then the transaction has been extended to the current global time. Extension by incremental validation is logically valid, because as long as the current stage of validation succeeds, transactions committed between the begin and the current global time does not write into the read set of the validating transaction. The serialization order between committed transactions and the validating transaction, therefore, is not defined until the validating transaction commits. If the incremental validation fails, the transaction must abort if it is an updating transaction, because the write phase must be performed on a most up-to-date snapshot.

For read-only transactions, the serialization condition can be less restrictive, as they do not update global state. Read-only transactions, if equipped with the ability to read older versions (the version storage itself must be multi-version enabled), can “time travel” backwards in the logical time. The result of such time travel is that the logical serialization order of read-only transactions could be even earlier than the logical time it starts. When a read is performed, the transaction tries to find the newest version whose lower bound is smaller than the transaction’s upper bound. If the version is available, and has been overwritten, then the transaction “closes” its upper bound, because it can no longer be extended (“time travel” forward in time). The upper bound of the read-only transaction is also set to either the upper bound of the transaction before the read operation, or the upper bound of the data item, whichever is smaller. If no such version is available, then the read-only transaction aborts.

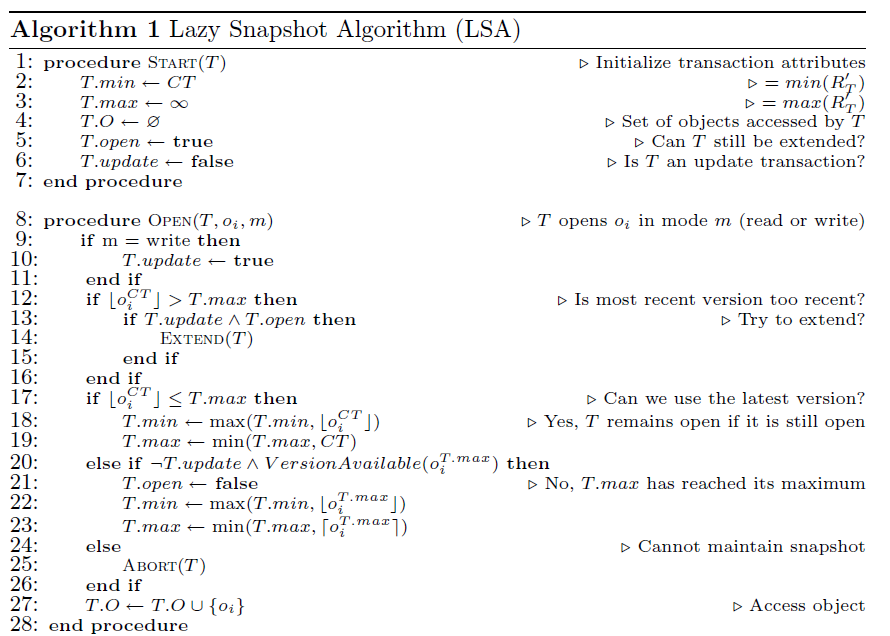

The paper gives a detailed description of the incremental BOCC algorithm, which is dubbed as the “Lazy Snapshot Algorithm” (LSA). Write phase is not covered in the description, nor does it give concrete solutions about the version storage, the garbage collection problem, etc. One of the interesting thing to note is that, although the paper claims that both the upper bound and the lower bound of the transaction is used to perform validation, only the upper bound appears meaningful in the algorithm description. The lower bound of the transaction, on the other hand, is only written into, but never read for purposes other than updating the lower bound itself. Removing the lower bound hence does not affect the correctness of the algorithm.

LSA commits more schedules compared with classical BOCC, where read-only transactions must commit strictly at the logical commit time. By allowing transactions to “read in the past” and restricting the maximum logical time to which read-only transactions are allowed to be extended, read-only transactions could “time travel” to the past without affecting serializability.

Compared with canonical TL2, the LSA algorithm allows transactions to read data items that are created after the logical begin time of a transaction. Different terminologies are used to describe these algorithms. The “begin timestamp” in TL2, used to describe the logical time at which the snapshot that the transaction hopes to operate on, is equivalent to the “txn.Max” variable in LSA. The “commit timestamp” of data items, used to describe the logical time at which a data item is created, is called the “lower bound” of an item at current logical time. The incremental validation scheme which adjustes the begin timestamp of transactions to the current logical time in TL2 is referred to as “extending txn.Max”.

Picture 1: LSA Algorithm Specification (Only partially shown)

Besides the differences in terminologies between LSA and TL2, these two algorithms also differ by several details in the pseudocode. First, the begin timestamp of a transaction in LSA is set to positive infinity, while in TL2 it is set to the current logical time. The reason for LSA to use positive infinity as the begin timestamp is that there is no “tentative” begin timestamp assigned, while in TL2 the tentative timestamp is exactly the current value of the global timestamp counter. In LSA, the begin timestamp of a transaction is derived as the result of the first access. In the algorithm presented by the LSA paper (and posted above), every transaction will hit line 17 on the first access to any data item, because txn.Max is infinite, and therefore the condition is always true. After hitting line 17, the begin timestamp is set as current logical time, which is essentially the same as TL2, but just uses the first access to data items as the logical begin time. The same effect can be achieved by setting txn.Max at transaction begin to current logical time, just like TL2. If this is the case, then on the first data item access, either line 12 or 17 will be hit. If line 12 is hit, then extend() will set txn.Max to current logical time as described earlier. If line 17 is hit, then txn.Max will be set to the minimum of txn.Max, or the current logical time. Since txn.Max itself must be smaller than or equal to the current logical time, so this line does not change txn.Max, and the net effect is still the same as TL2.

If we replace LSA’s terminology with those of TL2, the algorithm can be described as follows: On transaction begin, the begin timestamp is set to the current logical time. The reason that this does not change the algorithm’s behavior has been elaborated in the previous paragraph. On transactional read, the commit timestamp of the data item is compared with the current begin timestamp. If the former is greater, which means that the snapshot at begin timestamp is no longer valid, the algorithm tries to adjust the begin timestamp. The way of adjusting is to validate the read set. If data items in the read set have not be overwritten since they were read, then it makes no differnce if they were read at the current logical time. The current transaction could therefore “fake” a begin timestamp as the current logical time, and pretend that all the data items in the read set are read at the fake begin time. Of course, the validation phase must be carried out atomically, and no transaction commit would be allowed. If transactions commit during the validation phase, then possibilities exist that the read set is overwritten while the validation successfully adjusts the begin timestamp, which will commit non-serializable schedules. At a high level, by adjusting the begin timestamp on data item access, transactions essentially serializes itself after committed transactions regardless of the artificial begin timestamp. On the other hand, if the data item’s commit timestamp is less than the begin timestamp, then the data item is within the current snapshot of the transaction, and hence no adjustment is needed. The LSA algorithm requirs that the begin time be upper bounded by current logical time in this case at line 19. This line, however, is unnecessary as long as we do not use positive infinity as the initial begin timestamp, because the begin timestamp of a transaction is always less than or equal to the current logical time.