Adding Dynamic Github Contribution Calendar To Your Static Page

Introduction

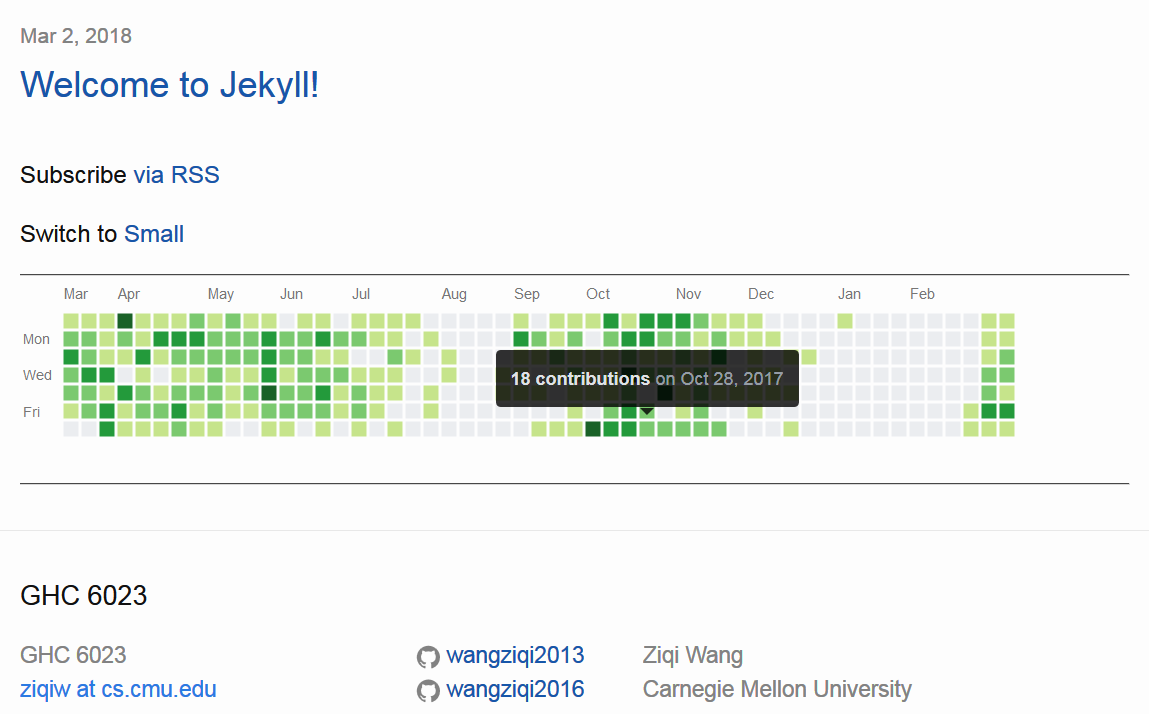

The contribution calendar is one of the nicest things on Github profile page. For crazy coders like many of my colleges, there is nothing more suitable to serve the purpose of showing off their hard work and devotion into the great cause that we call “programming”. This article aims at solving the problem of porting the dynamic-static Github contribution calendar onto your personal page. It is “dynamic” because the most recent update of your contribution history will be reflected the next time the page is refreshed. No effort of manually updating the calendar and even the static page itself is ever needed. It is “static” because no server-side programming is required. All you need is Javascript and ascynchronous XML HTTP request (XHR). In the following demonstration we use Github page (github.io domain) as the content provider. A preview of the final effect is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Preview

Disclaimer: I am not a web programmer, and I have not participated into any “serious” web development project. In the following discussion, incorrect/non-standard/risky practices may be stated in a form that underestimates the negative effects they can introduce. In addition, my HTML/JS/CSS coding style may also be non-standard or offensive to real web developers (I write good C/C++/Python, though). If you are unsure whether certain actions will bring about undesirable consequences, please refrain from conducting them. If extra clarification is needed, please consult a professional web developer or any other reliable sources.

Related Work

Obviously there are lots of diligent coders who treasure their Github contribution history. And when it comes to showing off, people are always motivated and innovative. Among many projects that mimic Github-style contribution calendar, the one that I like most is githubchart-api. The HTTP server, https://ghchart.rshah.org/[username], returns a static image that resembles the actual Github contribution calendar of [username]. The above link can therefore be embedded in an <img> tag. This solution is also dynamic-static.

Two problems can prevent the image-based contribution calendar from being authentic. First, lacking real HTML elements can lead to a few rendering problems. Customization is also impossible. Second, the user experience can be rather dull for lack of interaction. Normally, if you hang the mouse pointer over the green grid, a pop-up tip would appear as shown in Figure 1. A static picture, however, does not interact with users.

Methodology

Compared with image-based frontend or server-side backend approach, we strive to fulfill the following three requirements at the same time. First, the static content should be dynamic. This implies acquiring data from Github as the static page loads using asynchronous requests. Second, the contribution calendar should consist of HTML elements, and look excatly identical to the one on Github. This implies re-using the building blocks that Github profile page is written of, such as the HTML element layouts and CSS configurations. As we shall see later, it is helpful to look into the source of Github page. Lastly, the calendar should be interactive. This suggests implementing event listeners for the green grids. In this article, only mouse enter and mouse leave events are implemented as shown in Figure 1.

In the following sections, we present an implementation of the contribution calendar in static HTML, CSS and javascript. We first show how to insert the HTML elements dynamically. Then we show how to write the CSS for appropriately rendering these HTML elements. Finally, we add event handlers to support mouse events. A demonstration of the overall effects is uploaded to my Github page.

Obtaining HTML Elements

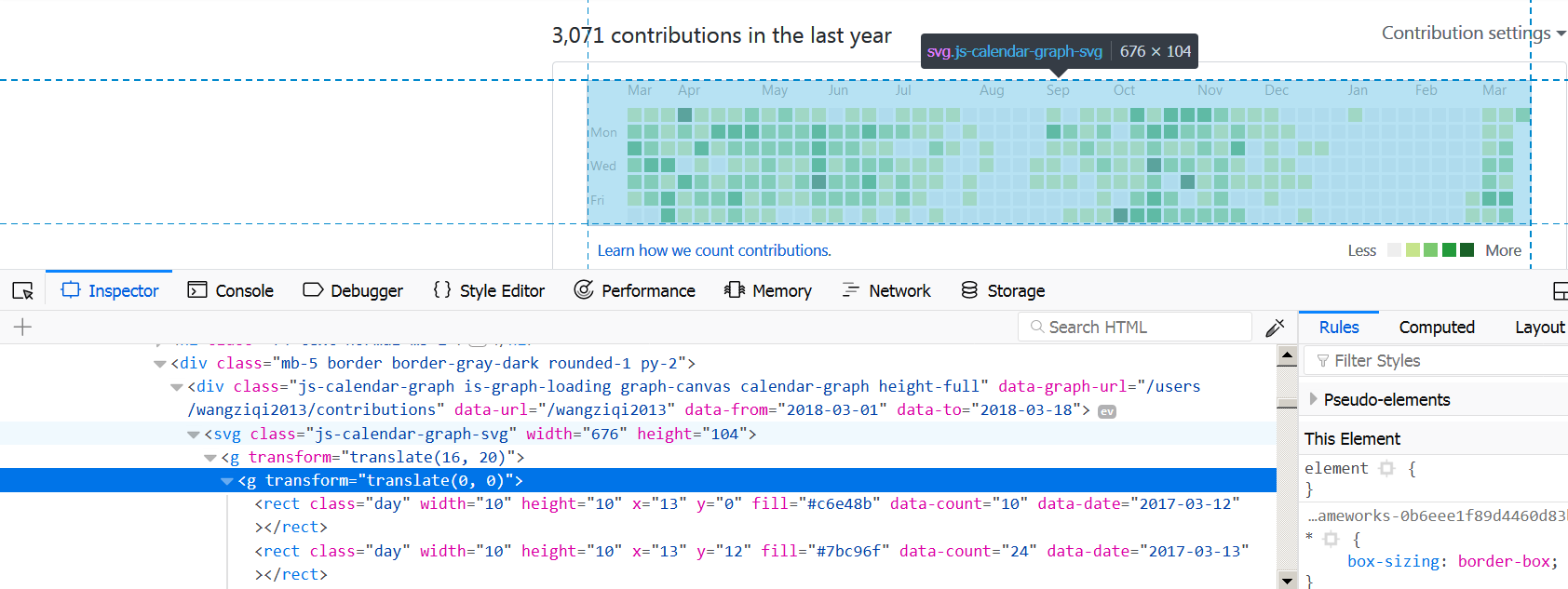

As said previously, the contribution calendar should consist of real HTML elements. By inspecting into the source code of the Github profile page, we should be able to find the HTML element that contains the calendar, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: HTML Elements

The entire calendar is wrapped inside an <svg> tag. “svg” stands for “Scalable Vector Graph”, which is an HTML 5 feature for drawing 2D shapes. All elements inside an SVG are treated as HTML DOM objects, and can be accessed programmatically by javascript. Daily contributions are rendered using the rectangle element, <rect>. Attributes of rectangles describe the metadata of the daily contribution, such as the contribution date, “data-date”, and commit count, “data-count”. Daily contributions are grouped together by the week they are in, using the containter element <g>. The entire calendar is then wrapped within a <g>. Texts that denote months and days in a week are drawn using <text>.

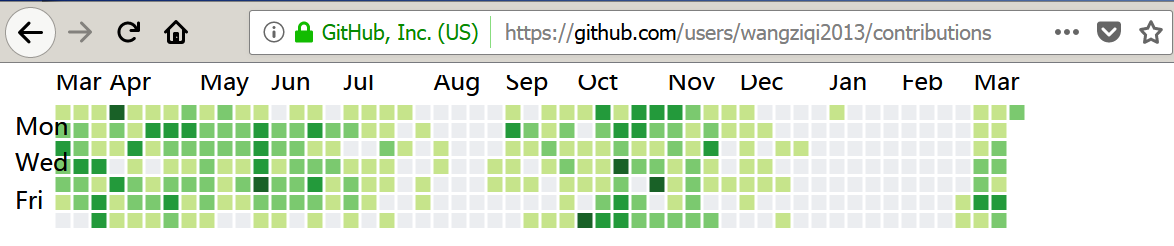

An attribute of the outermost <div> element in Figure 2 proves to be useful: “data-graph-url”. In our example, the Github user name is “wangziqi2013”, and the attribute’s value is therefore “/users/wangziqi2013/contributions”. If we enter the absolute URL “https://github.com/users/wangziqi2013/contributions”, the following will show up:

Figure 3: Graph Data URL

Apparently, what Figure 3 shows is the HTML source of Github’s contribution calendar with all metadata. Till now, we have solved the static part of the problem, i.e. how the elements are orgnized. Next, we focus on the dynamic part and seek ways of inserting the elements and metadata into the static page at runtime.

The technique we employ is called Asynchronous Javascript and XML (ajax). The design is straightforward: when the page is loading, a request for the aforementioned URL is sent by the browser. On reception of the response, HTML elements that constitute the calendar are parsed and inserted into the document. On most platforms, the asynchronous request can be handled using the built-in XMLHttpRequest (XHR) class.

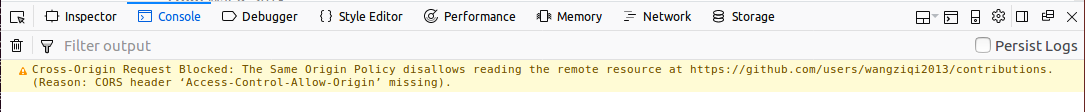

There is still one problem if the domain of your static page differs from the domain of Github, i.e. github.com, which is almost always the case. The XHR request to a different domain will actually be blocked by the browser to avoid some cross-site scripting attacks under the same-origin policy. An error message can be seen on the console if a cross-domain request is blocked by the brower, as shown in Figure 4.

Not all cross-domain requests, however, are blocked. Benevolent corss-domain requests, such as API calls, must be identified. The mechanism that browsers employ is called Cross Origin Resource Sharing (CORS). An extra HTTP header “Origin” with the current domain as value is added when the browser sends a cross-domain request. In the response header, if the current domain is allowed by the server on another domain, then there will be a header “Access-Control-Allow-Origin” (ACAO), which lists all allowed domains. If the current domain matches any of them (can be a wildcard, “*”), then the response can pass. Otherwise it is blocked.

Figure 4: Blocked Cross-Domain Request

Unfortunately, The Github web server does not reply with ACAO headers. There are CORS proxies, however, that forward requests/responses with CORS enabled. A simple search can find many of them. In our example we just choose one that works without any special reason: https://crossorigin.me/.

After solving the CORS problem, the javascript code that fetches the elements and metadata from Github server may look like this:

Code 1

function setContributionError(err_str) {

alert(err_str);

return;

}

function getAjax(url, success) {

var xhr = window.XMLHttpRequest ?

new XMLHttpRequest() :

new ActiveXObject('Microsoft.XMLHTTP');

xhr.open('GET', url, true);

xhr.responseType = "document";

xhr.onreadystatechange = function() {

if(xhr.readyState > 3) {

if(xhr.status == 200) {

success(xhr.responseXML);

}

}

return;

};

xhr.send();

return xhr;

}

function processHTML(text) {

var contri_div = text.getElementsByTagName("body");

if(contri_div.length != 1) {

setContributionError("Could not find contribution graph <div>");

return;

}

var target_div = document.getElementById("contributions");

if(target_div == null) {

setContributionError("Could not find target contribution <div>");

return;

}

target_div.innerHTML = contri_div[0].innerHTML;

// Explained later

var svg_list = target_div.getElementsByTagName("rect");

var total_count = 0;

for(var i = 0;i < svg_list.length;i++) {

var rect = svg_list[i];

rect.addEventListener("mouseover", onMouseEnter);

rect.addEventListener("mouseout", onMouseLeave);

// Count total contributions

total_count += parseInt(rect.getAttribute("data-count"));

}

// Show total contribution last year

var contri_count_div = document.getElementById("contri-count");

if(contri_count_div == null) {

return;

}

contri_count_div.innerHTML =

total_count.toString() + " contributions last year";

return;

}

xhr = getAjax("https://crossorigin.me/" +

"https://github.com/users/wangziqi2013/contributions",

processHTML);In the static page, we placed two empty <div> elements as placeholders. Their ids are set to “contri-count” and “contributions” respectively for displaying the total number of contributions in the last year and the calendar itself.

Adding CSS

CSS is another important part that we should add in order for the calendar to be authentic. Without CSS, the HTML elements will be rendered in a way similar to what is presented in Figure 3.

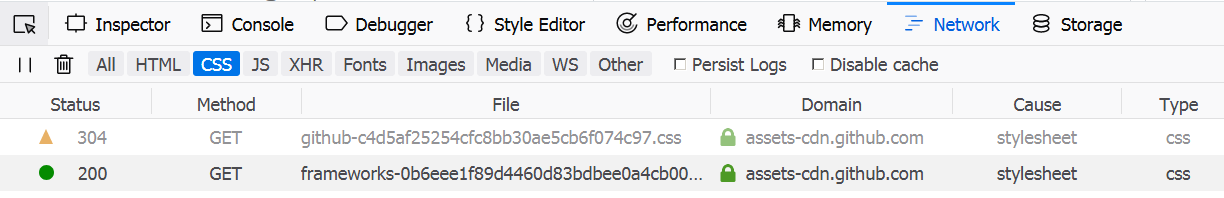

By keeping an eye on the network traffic, it is easy to find all CSS files that the Github profile page depends on. Figure 5 shows two CSS files.

Figure 5: CSS Files

The next step is rather mechanical. For each CSS file, search for keywords like “calendar”, which is the HTML class name

of the contribution calendar. Actually, only one file contains the keyword (the first one in Figure 5). Copy all selectors

that involve the calendar into the CSS file of your static page. The two most important selectors are .calendar-graph text.month and .calendar-graph text.wday which defines the text style. You may need to change the class name of the selector to something

like js-calendar-graph-svg in order to

match the actual HTML class (recall that we used a slightly different source of HTML elements). After adding CSS, the rendered

contribution calendar should look identical to the original one.

Code 2

.js-calendar-graph-svg text.month{font-size:10px;fill:#767676}

.js-calendar-graph-svg text.wday{font-size:9px;fill:#767676}User Interaction with Javascript

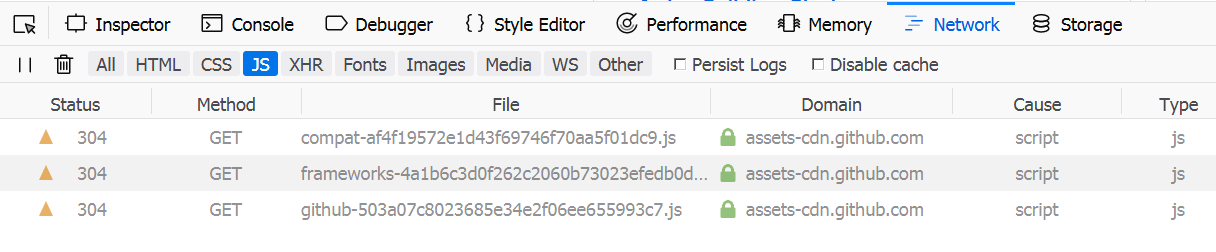

Javascript files can also be located using the network traffic monitor, as shown in Figure 6. The difficulty of searching within js files is that they are obfuscated. All variable names are replaced by meaningless mixture of letters, control flows are deliberately disturbed to avoid reverse engineering, and white spaces are removed to reduce file size. The only clue that we have are built-in function calls, and names of elements in the HTML documents, as they cannot be transformed by obfuscation.

Figure 6: Javascript Files

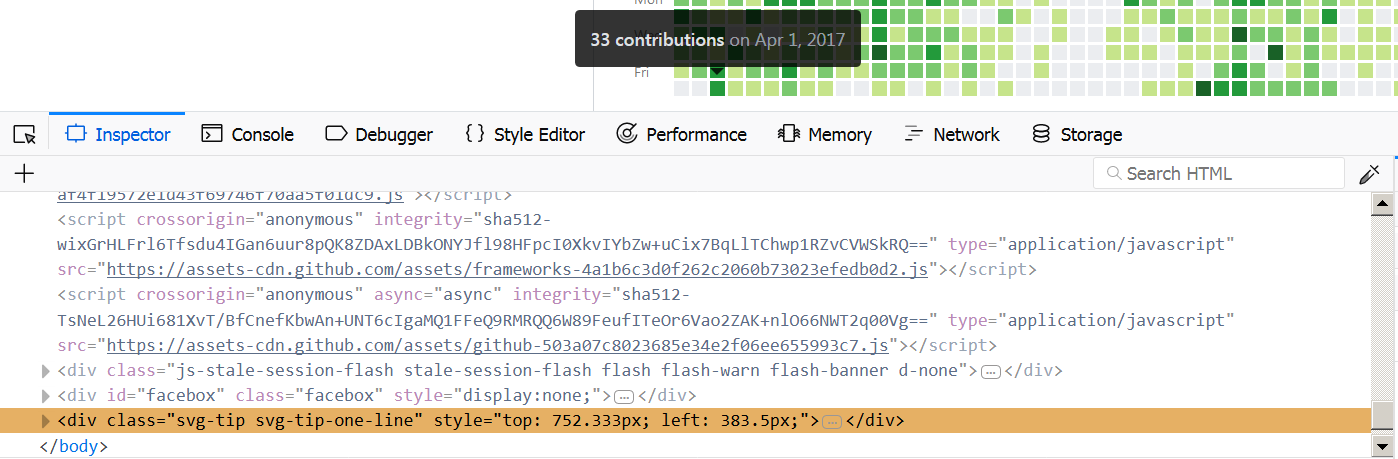

Let’s try moving the mouse pointer into and out of the grids, and see how the structure of the document would change.

As shown in Figure 7, at the bottom of the HTML document, a new element is created everytime the mouse pointer moves in,

and the element disappears everytime the point moves out. The element has a class attribute: svg-tip svg-tip-one-line.

Figure 7: The Tooltip Element

Using svg-tip-one-line as a keyword, exactly one match can be found in the third js file in Figure 6

(https://assets-cdn.github.com/assets/github-503a07c8023685e34e2f06ee655993c7.js). The matched line is

a.classList.add("svg-tip","svg-tip-one-line");, which looks pretty close. We use an online javascript

beautifier to add back white spaces. After processing, two functions seem highly relevant:

Code 3

function Pa(e) {

e.target.matches("rect.day") && (Na(), function(e) {

var n = document.body;

t(n, "null.js:91");

var r = e.getAttribute("data-date");

t(r, "null.js:94");

var a = function(e, t) {

var n = Tu[t.getUTCMonth()].slice(0, 3) +

" " + t.getUTCDate() + ", " + t.getUTCFullYear(),

r = 0 === e ? "No" : _.formatNumber(e),

a = document.createElement("div");

a.classList.add("svg-tip", "svg-tip-one-line");

var o = document.createElement("strong");

return o.textContent =

r + " " + P.pluralize(e, "contribution"), a.append(o, " on " + n), a

}(parseInt(e.getAttribute("data-count")), Va(r));

n.appendChild(a);

var o = e.getBoundingClientRect(),

s = o.left + window.pageXOffset - a.offsetWidth / 2 + o.width / 2,

i = o.bottom + window.pageYOffset - a.offsetHeight - 2 * o.height;

a.style.top = i + "px", a.style.left = s + "px"

}(e.target))

}

function Na() {

var e = document.querySelector(".svg-tip");

e && e.remove()

}It is quite trivial to see that function Na() removes the tooltip element. We register it as the mouseout

event listener for each rectangle element in the calendar SVG. Correspondingly, Pa() looks like a mouseenter

listener, not only because it creates the tooltip using document.createElement and sets its class

to svg-tip svg-tip-one-line, but also because of the event object in the argument.

After identifying the two major event listeners, the rest can be guessed out with medium effort. Function calls like

t(n, "null.js:91"); can be eliminated. The array Tu should be a list of month names as strings, because it

is indexed by UTC month and concatenated with strings. I changed _.formatNumber(e) to to e.toString(),

because variable e is e.getAttribute("data-count") in the outer scope which looks like the number of

contributions on a specific day. Similarly, P.pluralize(e, "contribution") basically adds an “s” after “contribution”

if the argument e is greather than 1. Although there is little clue about what Va(r) is, the function is

actually defined in the same file:

Code 4

function Va(e) {

var t = e.split("-").map(function(e) {

return parseInt(e, 10)

}),

n = ni(t, 3),

r = n[0],

a = n[1],

o = n[2];

return new Date(Date.UTC(r, a - 1, o))

}In the above code snippet, function ni is still unclear. Luckily, we know the input is a string of format “yyyy-mm-dd”

that represents a date. ni(t, 3) can be removed in this case, because it is likely just a function that pads/truncates

the array to length 3 after splitting the input using “-“ and converting each component into integer.

We post the final javascript below. Note that the addition of event handlers is in Code 1.

Code 5

function getDate(e) {

var t = e.split("-").map(function(e) {

return parseInt(e, 10)

}),

r = t[0],

a = t[1],

o = t[2];

return new Date(Date.UTC(r, a - 1, o));

}

function pluralize(num, word) {

if(num <= 1) {

return word;

} else {

return word + "s";

}

}

var month_name = ["January", "February", "March", "April", "May", "June",

"July", "August",

"September", "October", "November", "December"];

function onMouseEnter(e) {

e.target.matches("rect.day") && (onMouseLeave(), function(e) {

var n = document.body;

var r = e.getAttribute("data-date");

var a = function(e, t) {

// MMM DD, YYYY

var n = month_name[t.getUTCMonth()].slice(0, 3) +

" " + t.getUTCDate() + ", " + t.getUTCFullYear(),

// No contribution or a string

r = 0 === e ? "No" : e.toString();

// Create the element and add the class

a = document.createElement("div");

a.classList.add("svg-tip", "svg-tip-one-line");

var o = document.createElement("strong");

o.textContent = r + " " + pluralize(e, "contribution");

a.append(o, " on " + n);

return a;

}(parseInt(e.getAttribute("data-count")), getDate(r));

n.appendChild(a);

var o = e.getBoundingClientRect(),

s = o.left + window.pageXOffset - a.offsetWidth / 2 + o.width / 2,

i = o.bottom + window.pageYOffset - a.offsetHeight - 2 * o.height;

a.style.top = i + "px", a.style.left = s + "px"

}(e.target));

return;

}

function onMouseLeave() {

var e = document.querySelector(".svg-tip");

e && e.remove();

return;

}Also do not forget CSS for the tooltip class (it can be a superset of what is actually needed):

.svg-tip{position:absolute;z-index:99999;padding:10px;font-size:12px;color:#959da5;text-align:center;background:rgba(0,0,0,0.8);border-radius:3px}

.svg-tip strong{color:#dfe2e5}

.svg-tip.is-visible{display:block}

.svg-tip::after{position:absolute;bottom:-10px;left:50%;width:5px;height:5px;box-sizing:border-box;margin:0 0 0 -5px;content:" ";border:5px solid transparent;border-top-color:rgba(0,0,0,0.8)}

.svg-tip.comparison{padding:0;text-align:left;pointer-events:none}

.svg-tip.comparison .title{display:block;padding:10px;margin:0;font-weight:600;line-height:1;pointer-events:none}

.svg-tip.comparison ul{margin:0;white-space:nowrap;list-style:none}

.svg-tip.comparison li{display:inline-block;padding:10px}

.svg-tip.comparison li:first-child{border-top:3px solid #28a745;border-right:1px solid #24292e}

.svg-tip.comparison li:last-child{border-top:3px solid #2188ff}

.svg-tip-one-line{white-space:nowrap}

.svg-tip .date{color:#fff}Future Work

We did not implement the event handler for mouse click events. Essentially, if users click on the grid, then another ajax request should be sent to Github server to fetch the infomation of commits in that specific day.